👉👉 🇺🇸 All Posts 🇬🇧 / 🇯🇵 記事一覧 🇯🇵 👈👈

♦️ Conversation between a nurse and anesthesiologist

まっすー

まっすーDoctor, a nurse asked me: “What is the number in parentheses next to the blood pressure value?”

That’s a common question from new nurses. Did you explain about the mean arterial pressure (MAP)?

Of course I did!

♦️ What is Mean Arterial Pressure(MAP)?

Blood pressure is one of the most familiar vital signs. It’s even asked about in the anesthesiology board exam and the perioperative management team certification exam. Patients and nurses often bring it up, so we should understand it clearly.

Systolic blood pressure is 114 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure is 61 mmHg, and the mean arterial pressure is 77 mmHg. Whose blood pressure is this?

That’s mine—today’s blood pressure.

I thought it would be higher from stress.

It hurts to hear that… especially from the source of my stress!

Oops, I shouldn’t have said that…

MAP is the average pressure in the arteries during one cardiac cycle (systole + diastole).

- SBP and DBP are the maximum and minimum pressures.

- MAP is the time-weighted average pressure.

- Think of it as the real blood pressure that drives blood flow to organs.

So when anesthesiologists say “Maintain the MAP,” what they really mean is “Maintain organ perfusion,” right?

Exactly. Clinically, we often aim for a MAP ≥ 65 mmHg. In elderly patients, vasopressors are frequently needed. For patients with chronic hypertension, an even higher MAP may be necessary.

Your MAP looks fine, Doctor.

That’s because I’m still young.

Aren’t you actually older than you look…?

♦️ SBP, DBP, and MAP

Can we also review systolic and diastolic pressures?

Systolic blood pressure (SBP): pressure when the heart contracts, the “upper number.”

Diastolic blood pressure (DBP): pressure when the heart relaxes, the “lower number.”

So MAP is just the midpoint between them? Like (120 + 80)/2 = 100 mmHg?

That’s what people usually think, but it’s not that simple.

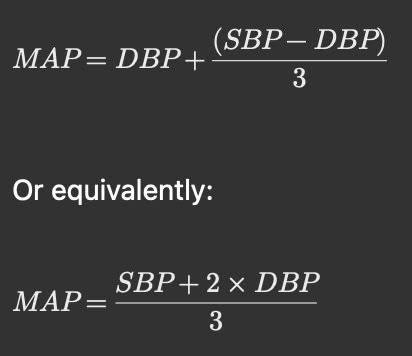

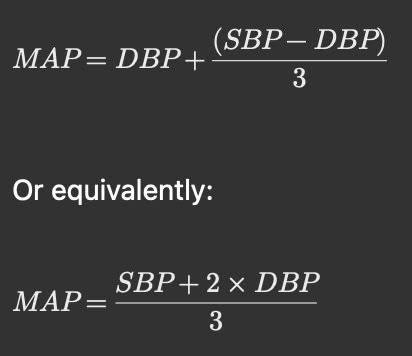

Because the heart spends more time in diastole than systole, MAP is closer to DBP. The common formula is below.

So diastole is weighted more heavily! Let me try with your numbers: (114 + 61×2) ÷ 3 = about 78.

This comes from the fact that about two-thirds of the cardiac cycle is spent in diastole.

Exactly. Automated monitors use oscillometric algorithms, so the displayed MAP may differ slightly, but it’s close.

♦️ MAP and Organ Perfusion

Can you go over the relationship between MAP and organ blood flow again?

Sure. MAP is the driving pressure that pushes blood into the organs. To keep organs functioning, we need at least about 60–65 mmHg. Normally MAP is around 70–100 mmHg. If MAP drops below this range for long, organ perfusion can fail.

And if organ perfusion fails, what happens?

Brain → risk of ischemia

Kidneys → oliguria or anuria

Heart → myocardial ischemia

This can become life-threatening. Short, mild drops may not cause immediate harm, but prolonged or severe drops are dangerous—especially in elderly patients with less reserve.

True. In septic or hemorrhagic shock, MAP can be very low intraoperatively, but sometimes patients recover without deficits.

What about dizziness when standing up?

That’s transient MAP drop → temporary cerebral ischemia → dizziness. Stand up slowly, especially elderly patients—they can faint and fracture bones.

♦️Shock and MAP

If MAP remains low, organ dysfunction develops. Particularly kidney failure, brain ischemia, and myocardial ischemia are critical.

When patients are in shock from bleeding, I often see tachycardia and cold extremities.

Exactly.

Tachycardia = the heart trying to maintain cardiac output.

Cold extremities = vasoconstriction, shunting blood away from skin to protect brain and heart.

So should we just give vasopressors whenever MAP is low?

Not always. You need to identify the cause.

There are many causes of shock: hypovolemic shock (including hemorrhagic shock), cardiogenic shock such as myocardial infarction, obstructive shock like pulmonary embolism, and distributive shock due to conditions such as sepsis, anaphylaxis, or neurogenic shock (where the blood vessels are dilated). Treatment must be tailored to the underlying cause, otherwise the patient’s condition may worsen.

Types of shock and typical treatments:

- Hypovolemic shock (incl. hemorrhage): fluids, blood transfusion, often vasoconstrictors.

- Cardiogenic shock (e.g., MI): treat cause, consider inotropes/vasopressors.

- Obstructive shock (e.g., pulmonary embolism, tamponade): treat obstruction, supportive therapy.

- Distributive shock (e.g., sepsis, anaphylaxis, neurogenic shock): treat cause + norepinephrine or other vasopressors.

Some people just silence the alarm and push ephedrine or phenylephrine without thinking. That’s absolutely wrong. You must treat the underlying cause.

Wait, are you talking about someone in particular?

…I’m not naming names.

♦️ Wrapping up

So the number in parentheses, MAP, is the pressure ensuring blood reaches vital organs.

Exactly. If MAP falls, organs like brain, kidney, liver, and heart lose adequate perfusion, impairing oxygen delivery and organ function.

During anesthesia, blood pressure tends to drop.

Yes, especially in elderly patients with hypertension and comorbidities. That’s why appropriate fluids, transfusion, and vasopressors are needed. Blood pressure and hemodynamic management are deep topics—we can’t cover everything in one session. Keep asking questions!

📝 Summary

- MAP is a key indicator of organ perfusion.

- Anesthetized patients often experience hypotension; maintaining MAP is critical.

- Causes of low MAP vary → treatment must target the cause, not just symptoms.

- Aim for MAP ≥ 60–65 mmHg to ensure vital organ blood flow.

🔗 Related articles

📚 References & Links

- Cecconi M, De Backer D, Antonelli M, et al. Consensus on circulatory shock and hemodynamic monitoring. Task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(12):1795–1815. DOI: 10.1007/s00134-014-3525-z

- Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(3):304–377. DOI: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6

- Asfar P, Meziani F, Hamel JF, et al. (SEPSISPAM trial). High versus low blood-pressure target in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(17):1583–1593. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312173

- De Backer D, Biston P, Devriendt J, et al. (SOAP II trial). Comparison of dopamine and norepinephrine in the treatment of shock. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:779–789. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907118

- Vincent JL, De Backer D. Circulatory shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1726–1734. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1208943

コメントを投稿するにはログインしてください。