👉👉 🇺🇸 All Posts 🇬🇧 / 🇯🇵 記事一覧 🇯🇵 👈👈

♦️ The Frightening Reality of Hypertension 😨

Hypertension, often called the “silent killer,” typically causes no obvious symptoms. Yet it is a major risk factor for numerous diseases and organ damage. Examples include:

- Cerebrovascular disease: subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage, ischemic stroke

- Cardiovascular disease: myocardial infarction, aortic dissection, left ventricular hypertrophy, heart failure, arrhythmias (such as atrial fibrillation)

- Kidneys: chronic kidney disease

While not every mildly elevated blood pressure reading requires aggressive pharmacologic intervention, persistently high pressures—such as ≥180/110 mmHg—pose significant danger if left untreated.

Rather than reviewing hypertension in general (many excellent reviews already exist), let’s focus here on what anesthesiologists need to know when managing patients with hypertension.

♦️ Antihypertensive Medications 💊

Most hypertensive patients are taking one or more of the following medications:

- Calcium channel blockers (e.g., Amlodipine, Diltiazem)

- Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) (e.g., Losartan, Valsartan)

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) (e.g., Enalapril, Lisinopril)

- β-blockers (e.g., Metoprolol, Carvedilol)

Patients with ischemic heart disease or arrhythmias often require multiple agents.

β-blockers lower heart rate. When combined with commonly used anesthetic agents—especially opioids like remifentanil, which also tends to cause bradycardia—patients are at increased risk of excessive heart rate suppression. Importantly, abrupt discontinuation of β-blockers can provoke rebound hypertension or ischemia, so they should generally be continued perioperatively.

Other anesthetic agents that can significantly reduce heart rate include dexmedetomidine, often used for sedation.

ACE inhibitors and ARBs are associated with exaggerated intraoperative hypotension when continued on the day of surgery. For this reason, many institutions advise holding them on the morning of surgery, though some guidelines allow continuation.

Ultimately, this decision should follow institutional protocol. In contrast, calcium channel blockers are typically continued.

♦️ Key Perioperative Considerations

🔷 It’s Not Just “High Blood Pressure” That Matters

Inside the OR, the absolute blood pressure number at that moment is not the only concern. The real issue is the chronic exposure to elevated blood pressure.

🔷 Autoregulation of Vital Organ Blood Flow

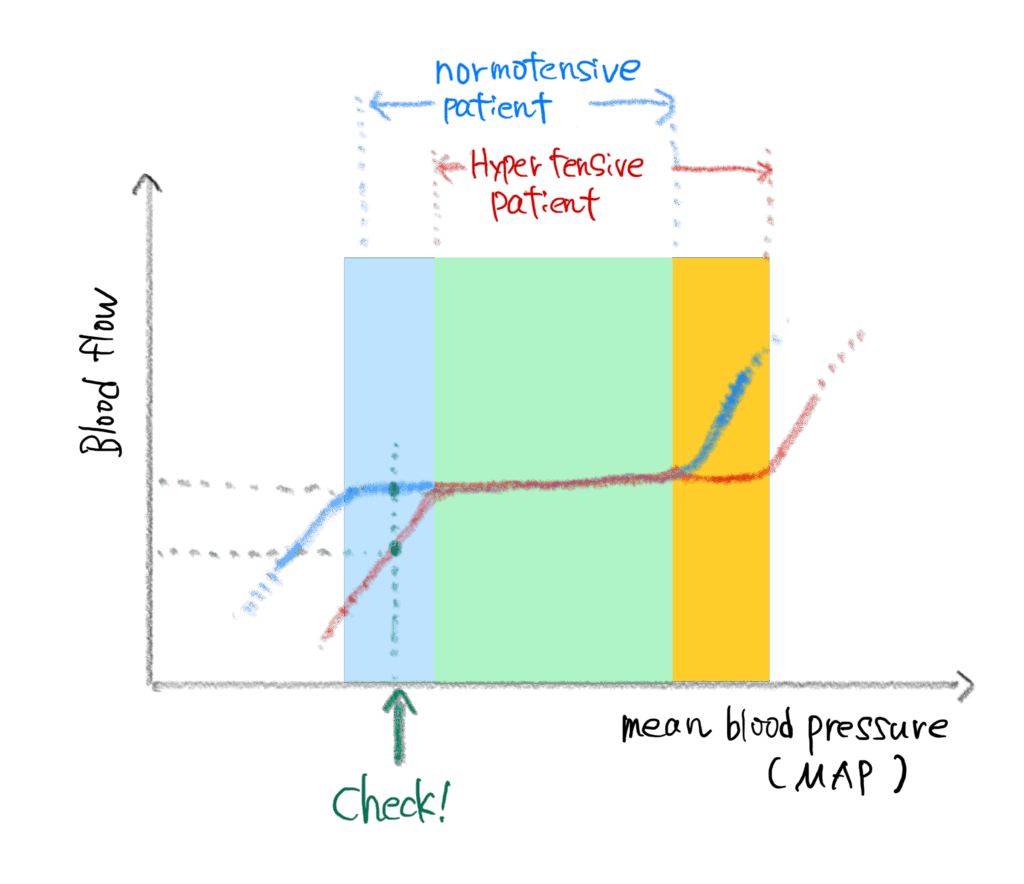

☝️Organ blood flow autoregulation — Blue: Normotensive, Red: Chronic hypertension

Many organs (not all) have the ability to maintain relatively constant blood flow despite fluctuations in systemic blood pressure—this is called autoregulation. Thanks to this mechanism, modest changes in blood pressure usually do not cause ischemic injury.

☝️ Note: Autoregulation is particularly critical in the brain, kidneys, and heart. Not every organ possesses strong autoregulatory capacity.

In chronic hypertension, the autoregulatory curve shifts to the right. Organs adapt to the higher baseline blood pressure, meaning that what would be a “tolerable” hypotension in a normotensive patient may actually cause ischemia in a hypertensive one.

- In a healthy individual, organ blood flow is maintained across a wide range of pressures.

- In a chronically hypertensive patient, the “safe zone” is shifted upward.

Focus on the green check mark. At that blood pressure, blood flow is reduced in hypertensive patients.”

Thus, blood pressures that would be acceptable for normotensive patients may be inadequate for those with chronic hypertension, leading to reduced organ perfusion.

Moreover, because hypertensive patients often have coexisting cerebrovascular or coronary artery disease, even brief hypotension can precipitate myocardial or cerebral ischemia.

☝️ Interestingly, patients whose blood pressure is well controlled medically may regain near-normal autoregulation ranges.

♦️ Hemodynamic Instability During Surgery

If you’ve worked in the OR, you’ve probably noticed: hypertensive patients—especially the elderly or those with poorly controlled hypertension—exhibit marked blood pressure variability.

One moment, their systolic pressure is 150 mmHg; immediately after induction, it plummets to 70 mmHg. Hypertensive patients often respond exaggeratedly to anesthetics and vasoactive drugs.

If management lags behind, the result can be the so-called “rollercoaster anesthesia”—repeated cycles of hypertension and hypotension. Such swings are clearly harmful to vital organs.

📝 Take-Home Points

- Hypertensive patients are often on multiple medications, which can influence perioperative vital signs.

- ACE inhibitors/ARBs: many institutions advise withholding on the day of surgery, though continuation is permitted by some guidelines—follow your institution’s policy.

- β-blockers: continue perioperatively (abrupt withdrawal is dangerous).

- Chronic hypertension shifts organ blood flow autoregulation upward, increasing ischemia risk with hypotension.

- Hypertension is frequently associated with comorbidities (cardiac and cerebrovascular disease).

- Intraoperative blood pressure fluctuations are exaggerated, requiring vigilant management.

🔗 Related articles

- to be added

📚 References & Further reading

- 2022 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular assessment and management of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery European Heart Journal. 2022;43(39):3826-3924. https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/43/39/3826/6674438

- 2023 AHA/ACC/ACS/ASNC/HRS/SCA/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for Perioperative Cardiovascular Management for Noncardiac Surgery Circulation. 2023;148:e369–e467. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001166

コメントを投稿するにはログインしてください。