👉👉 🇺🇸 All Posts 🇬🇧 / 🇯🇵 記事一覧 🇯🇵 👈👈

♦️ Introduction

さらりーまん

さらりーまんThat patient has a history of moderate bronchial asthma … I don’t want to make them wheeze with intubation.

We’ll ask them to use their β₂ agonist and inhaled steroids before surgery. Shall we use an SGA (supraglottic airway)?

SGA may cause less airway stimulation, but if an asthma attack happens, it might get tricky. Let’s go step by step — preoperative evaluation/optimization, anesthesia plan, and handling intraoperative bronchospasm.

♦️ Asthma – Summary

Asthma is a chronic airway inflammatory disease in which the airway becomes hyperreactive; trivial stimuli provoke reversible airflow limitation (especially on expiration). Eosinophilic inflammation (IL-4/5/13), airway remodeling (basement membrane thickening, smooth muscle hypertrophy, increased mucus production) play key roles, and symptoms often worsen at night, with exercise, or during viral infections.

Diagnosis hinges on symptom variability and reversible airflow obstruction on spirometry (e.g. increase in FEV₁ of ≥200 mL and ≥12 %). Treatment includes β₂ agonists, inhaled corticosteroids, and other controller medications. Aspirin‐exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD) is a risk: NSAIDs can provoke abrupt worsening, so that history must be elicited carefully.

In the perioperative period, the greatest risk of bronchospasm is during induction, airway manipulation, and emergence.

♦️ Perioperative Evaluation & Optimization – 90% is here

🔷 Important History & Physical Findings

- Recent exacerbations: ER visits, hospitalizations, prior intubations?

- Frequency of nocturnal cough, dyspnea on exertion

- SABA usage (is it > 2×/week?)

- Recent respiratory infection (if present, consider postponement)

- Adherence to medications and inhaler technique

- History of NSAID worsening (AERD risk)

If wheezing on auscultation or prolonged expiratory phase is present, or control is suboptimal, avoid elective surgery and optimize first.

🔷 Optimization Strategies 📝

- Continue inhaled therapy (ICS, LABA if applicable).

- Smoking cessation if applicable (ideally > 6–8 weeks prior to surgery to allow mucociliary recovery).

- In cases of poor control, consider a short course of systemic steroids preoperatively; if chronic steroids are present, consider adrenal suppression and plan stress‐dose steroids.

- Just before entering the OR, have the patient inhale a SABA — evidence supports reducing airway resistance and wheezing after intubation.

♦️ Anesthesia Plan: Minimize Airway Stimulation

🔷 Choice of Anesthesia Modality

Whenever feasible, use regional anesthesia (peripheral nerve block, spinal/epidural) as first choice. If general anesthesia is unavoidable, plan to minimize airway manipulation.

🔷 Airway Devices

A supraglottic airway tends to provoke less airway stimulation and lower respiratory resistance compared to endotracheal intubation, so prefer it when appropriate. However, always have plans for conversion to intubation if bronchospasm or airway compromise occurs.

If intubation is needed, ensure deep anesthesia and “gentle” technique. Some centers give intravenous lidocaine 1.5–2 mg/kg about 90 seconds before intubation to blunt cough and circulatory reflex.

🔷 induction & Maintenance Agents

There is no absolute “forbidden” agent among modern anesthetics, but choices matter:

- Propofol: suppresses airway reflexes and has mild bronchodilating effect — often first choice

- Ketamine: potent bronchodilator, useful especially in hemodynamically unstable cases (but beware secretion increase)

- Volatiles (sevoflurane, isoflurane): have bronchodilatory effects and are commonly used for maintenance

- Desflurane: known to irritate airway and increase resistance at higher concentrations — avoid if possible in asthmatic patients

🔷 muscle Relaxants & Reversal

- Nondepolarizing relaxants with minimal histamine release (e.g. rocuronium, vecuronium, cisatracurium) are preferred.

- Some authors caution against histamine‐releasing relaxants (e.g. atracurium, mivacurium) in susceptible patients.

- For reversal: sugammadex (for steroidal relaxants) is favored over neostigmine in many modern settings because it avoids muscarinic side effects (which might exacerbate bronchospasm) and offers more rapid, predictable reversal.

- Indeed, some literature warns that neostigmine theoretically may exacerbate bronchoconstriction in wheezing patients, so prefer sugammadex if available and indicated.

🔷 Ventilation Strategy

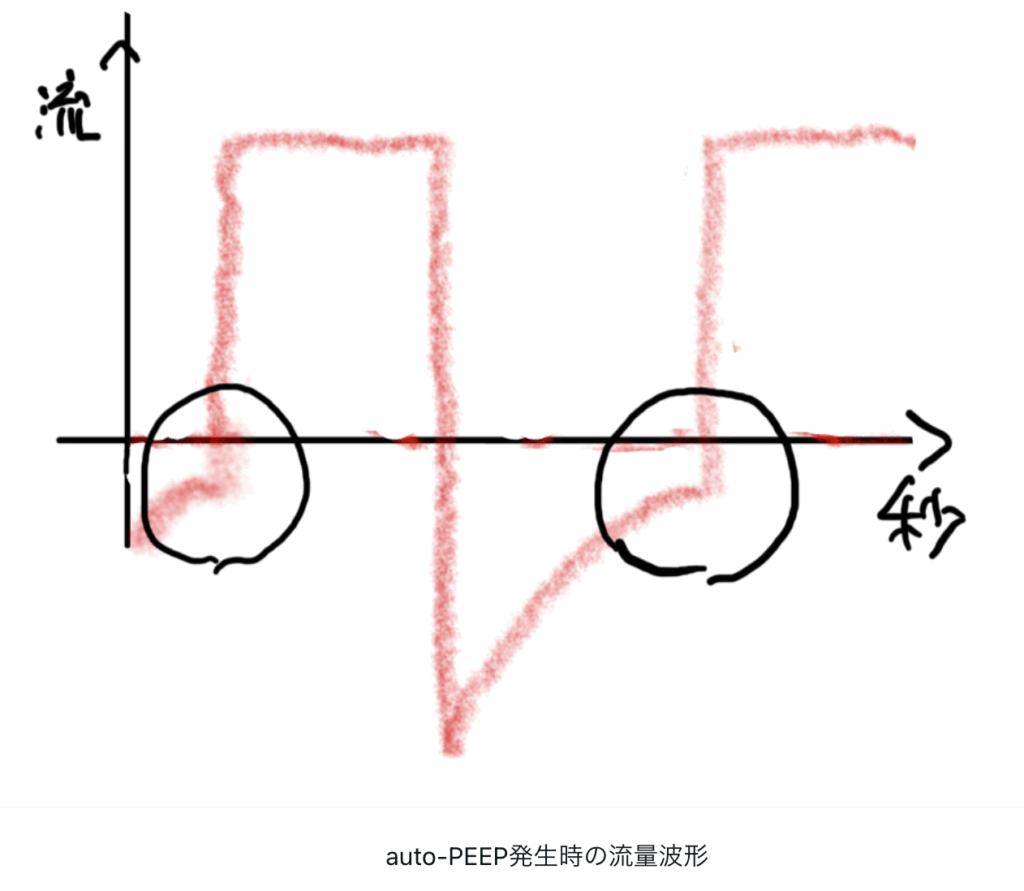

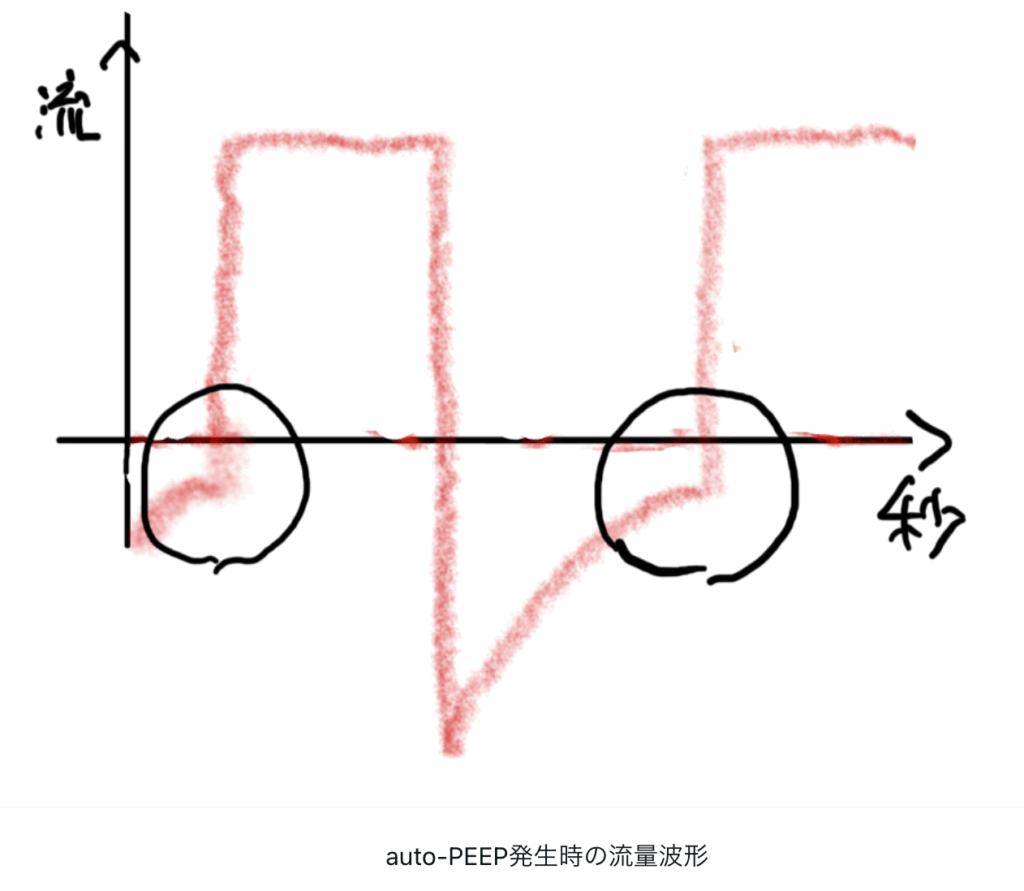

The key is to allow sufficient exhalation and avoid gas trapping (auto-PEEP).

- Use I:E ratios of 1:3 to 1:4

- Use relatively low respiratory rates and tidal volumes (4–6 mL/kg) to give patients time to exhale fully

- In severe cases, permissive hypercapnia is acceptable

- Monitor flow waveforms; if the expiratory limb does not return to baseline before the next breath, that suggests auto-PEEP. In extreme cases, consider temporarily disconnecting the circuit to decompress the trapped gas.

🔷 Emergence & Extubation

The emergence period is high risk for bronchospasm.

- Some centers extubate under deeper anesthesia, but evidence is limited.

- Clear secretions before extubation, and consider giving a SABA inhalation around extubation.

- For analgesia, avoid histamine‐releasing opioids (e.g. morphine) if possible; favor fentanyl, acetaminophen, or regional analgesia.

- Avoid NSAIDs if AERD is suspected or uncertain.

♦️ What If Bronchospasm Happens Intraoperatively? 😫

- Switch to 100 % O₂ and manual ventilation

- Exclude mechanical causes (tube obstruction, circuit problem, endobronchial intubation, pneumothorax)

- Deepen anesthesia (increase volatile agent, or infuse propofol / ketamine)

- Administer β₂ agonists (via MDI through the circuit or nebulizer)

- Add anticholinergics (e.g. ipratropium) if needed

- Administer IV steroids (though their onset is delayed, they help prevent recurrence)

- In refractory cases: small-dose IV epinephrine, or magnesium sulfate bolus (some evidence suggests benefit in resistant cases)

📝 Summary: Take Home Points

- Preoperative assessment and optimization is critical.

- Avoid elective procedures if asthma control is poor, and always reconcile steroid history and adrenal suppression.

- Minimize airway stimulation (prefer regional if possible, or SGA over ETT).

- Use a SABA inhalation just prior to entering OR.

- Choose anesthetic agents favoring bronchodilation (propofol, ketamine, sevoflurane) and avoid desflurane in most asthmatics.

- Use sugammadex over neostigmine for reversal when possible, especially in wheezing patients.

- Ventilate slowly, allow prolonged exhalation, monitor for auto-PEEP.

- If bronchospasm occurs: deepen anesthesia, administer β₂ agonists ± anticholinergics, steroids, and escalate to epinephrine or magnesium if needed.

- Sugammadex is widely used in many developed countries but its availability and cost may limit its use in some settings.

- The choice between deep vs awake extubation is controversial and often institution‐dependent.

- In some guidelines, preoperative spirometry beyond baseline may not always alter decision-making unless the patient is symptomatic.

📚 References & Further reading

- OpenAnesthesia (2024) Anesthesia for Patients with Asthma Open Access (Latest expert practical guidance on anesthesia management in asthma)

- Bayable SD et al. (2021) Perioperative management of patients with asthma Open Access – PubMed Central (Comprehensive review covering step-by-step perioperative care)

- StatPearls (2024) Anesthesia Management in Asthma Open Access (Concise clinical synthesis, regularly updated)

- Thejane F (2022) Asthma and Anesthesia Open Access, PDF (Recent guidance and summary slides for clinicians)

- Enright PL (2008) COPD and Asthma Guidelines (J Anesth 22:412–428) Open Access, PDF (Guideline-based preoperative recommendations)

- Healthline (2021) Asthma and Anesthesia: What Are the Risks? Open Access (General clinical advice, easily readable)

- Kim ES, Bishop MJ (1999) Endotracheal intubation, but not laryngeal mask airway insertion, produces reversible bronchoconstriction (Foundational study on airway manipulation and bronchospasm risk)

- Rajesh MC (2004) Anaesthesia for children with bronchial asthma Open Access – PubMed Central (Pediatric-specific focus)

- 10. Kil HK, Rooke GA, Ryan-Dykes MA, Bishop MJ (1994) Effect of prophylactic bronchodilator treatment on lung resistance after tracheal intubation (Key evidence for pre-intubation bronchodilator)

🔗 Related articles

- to be added

コメントを投稿するにはログインしてください。